This article is a guest post written by Brian Eckert. Guest writers contribute to our blog in their personal capacity. The views expressed are their own and do not necessarily represent the views of Didomi.

Do you have something to share and are interested to be featured? Get in touch at

Almost anyone above a certain age can remember the first time they connected to the Internet via dial-up. There was a strange sound, like a combination of a fax machine and a washing machine, and then, suddenly, you were “online” and connected to the World Wide Web, with the vast sum of human knowledge at your fingertips, if only you knew where to look.

From the Internet’s public rollout to now, the amount of data generated has grown exponentially, from petabytes to zettabytes, driven by user-generated content, smartphones, social media, and the Internet of Things (IoT).

This explosion of information gave rise to the concept of Big Data and the need to manage extremely large and complex data volumes. It also helped spur the modern data privacy movement and the laws that followed, as more of our lives moved online, often in ways that felt beyond our control.

Another momentous development in the digitization and “internetization” of things arrived in November 2022 with the debut of ChatGPT. For many people, the AI chatbot was their first direct interaction with generative AI. Trained on vast swaths of online data, it allowed users to navigate the ever-deepening oceans of information in a more direct and responsive way than traditional search engines.

AI is the logical (one could even say inevitable) outgrowth of Big Data. But its widespread adoption in just a few short years has raised new questions about data privacy at a time when both privacy laws and AI models are continually being rewritten. It has also added to the feeling that we’re losing control of systems that were meant to help us regain it.

For companies, the convergence of overlapping state privacy laws, emerging AI-specific regulations, and growing federal interest in preemption has made compliance a moving target, one that is shifting faster than many governance frameworks and existing tools were designed to address.

The “AI cambrian explosion”

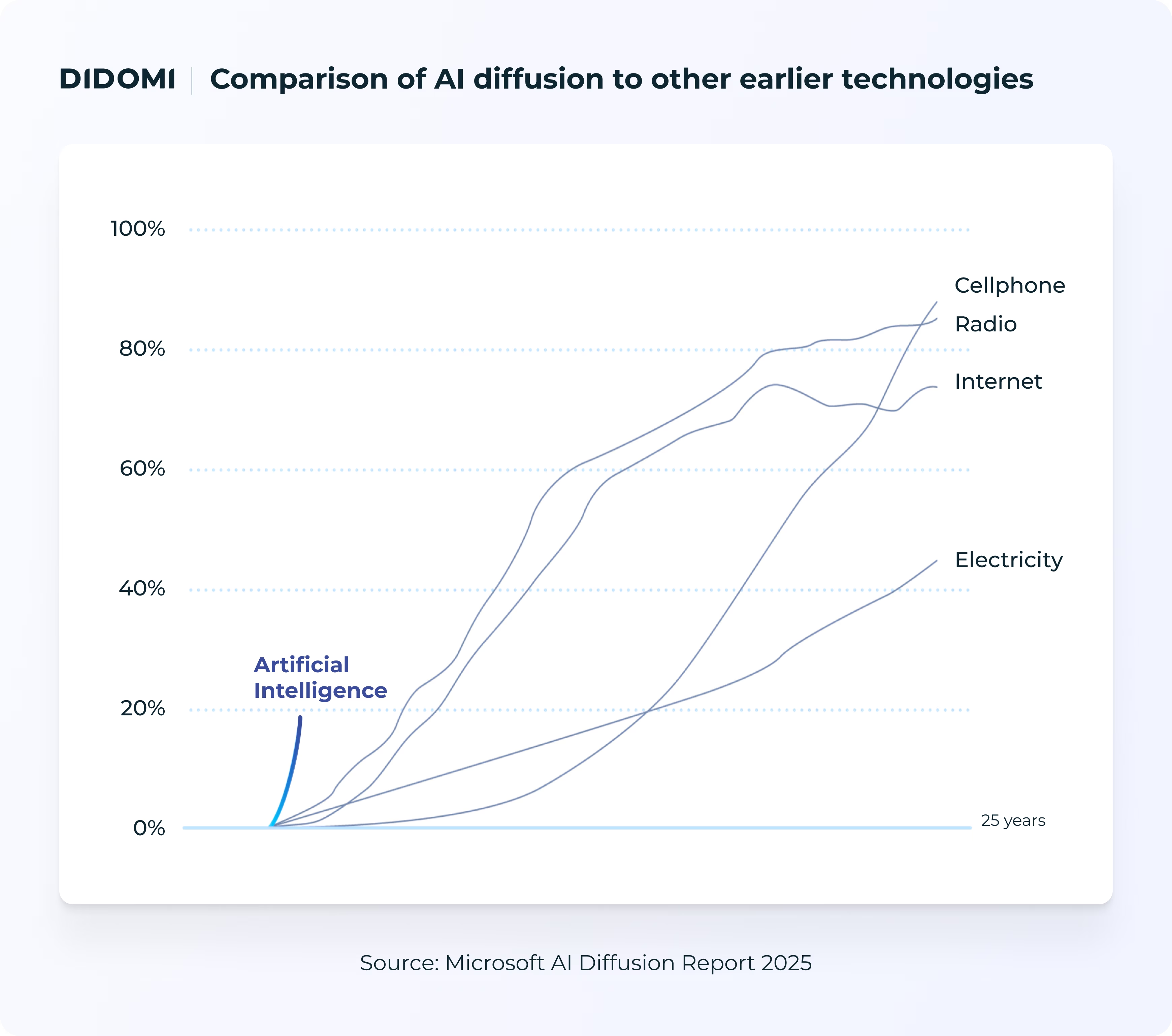

From nearly the moment it was released to the public, AI and its many iterations have proliferated at an unprecedented pace, even faster than the personal computer (PC) and the Internet before it.

Since ChatGPT’s launch, hundreds, if not thousands, of AI models have emerged from major tech companies and countless startups, resulting in a “Cambrian explosion” in the field of generative AI. While it took the PC three years to reach a 20% adoption rate and the Internet three years to reach the same milestone, 40% of Americans were using generative AI just two years after ChatGPT was introduced.

To put the pace of AI adoption in perspective, the Internet took decades to mature into a commercial backbone of the global economy. AI reached 100 million users in just two months.

By 2025, roughly 78% of companies worldwide reported using AI in at least one business function. At that level of adoption, AI is already integrated into operations across hundreds of millions of businesses globally, including widespread use among small businesses relying on AI tools for everyday tasks.

The speed with which AI has become mainstreamed, and the transformative potential AI brings to every sector, is only beginning to be reckoned with creatively, economically, and legally.

What the Cambrian explosion achieved in evolutionary terms over 540 million years has, in technological terms, been compressed into a handful of years by AI. And continuous breakthroughs in the emerging “AI arms race” mean that the pace of AI-driven change may only accelerate as companies increase their investments. It is a technological evolution, and evolution produces winners and losers.

AI as a privacy threat vector

Some of the privacy issues inherent to the Internet weren’t apparent right away. Its initial development often prioritized functionality and open information exchange over privacy, and early privacy law efforts lagged behind companies’ data-collection capabilities. It frequently felt as though regulators were playing catch-up, and, in many respects, that dynamic persists today.

Using 1993 as a rough date for when the Internet floodgates opened, it took a quarter century for the world’s first comprehensive privacy law, Europe’s 2018 GDPR, to grapple with many of the privacy issues of the online era. Since then, privacy laws have spread at scale and speed across the globe.

But that rate of proliferation is still no match for the pace of technological change.

Lawmaking is part of a process that is open to democratic participation and subject to transparency. Laws must pass through subcommittees and multiple rounds of votes and revisions just to be considered. New technology, however, is developed behind closed doors, protected from scrutiny by intellectual property laws, and comes online when private companies decide to do so. Engineers and executives, not lawmakers and voters, approve it. And profits move far faster than public policy ever can.

We still aren’t privy to Google’s search algorithm, let alone its AI training methods or model-use protocols. There is no broad legal requirement compelling Google, OpenAI, or any other AI company to publicly disclose their AI algorithms or the full details of how their models are trained (including source code or proprietary architecture) outside specific regulatory actions or litigation.

“Move fast and break things” (the unofficial mantra of many technology companies) has a tendency to prevail over “slow down and limit damage,” which is what many privacy experts, tech advocates, policymakers, and consumers would prefer.

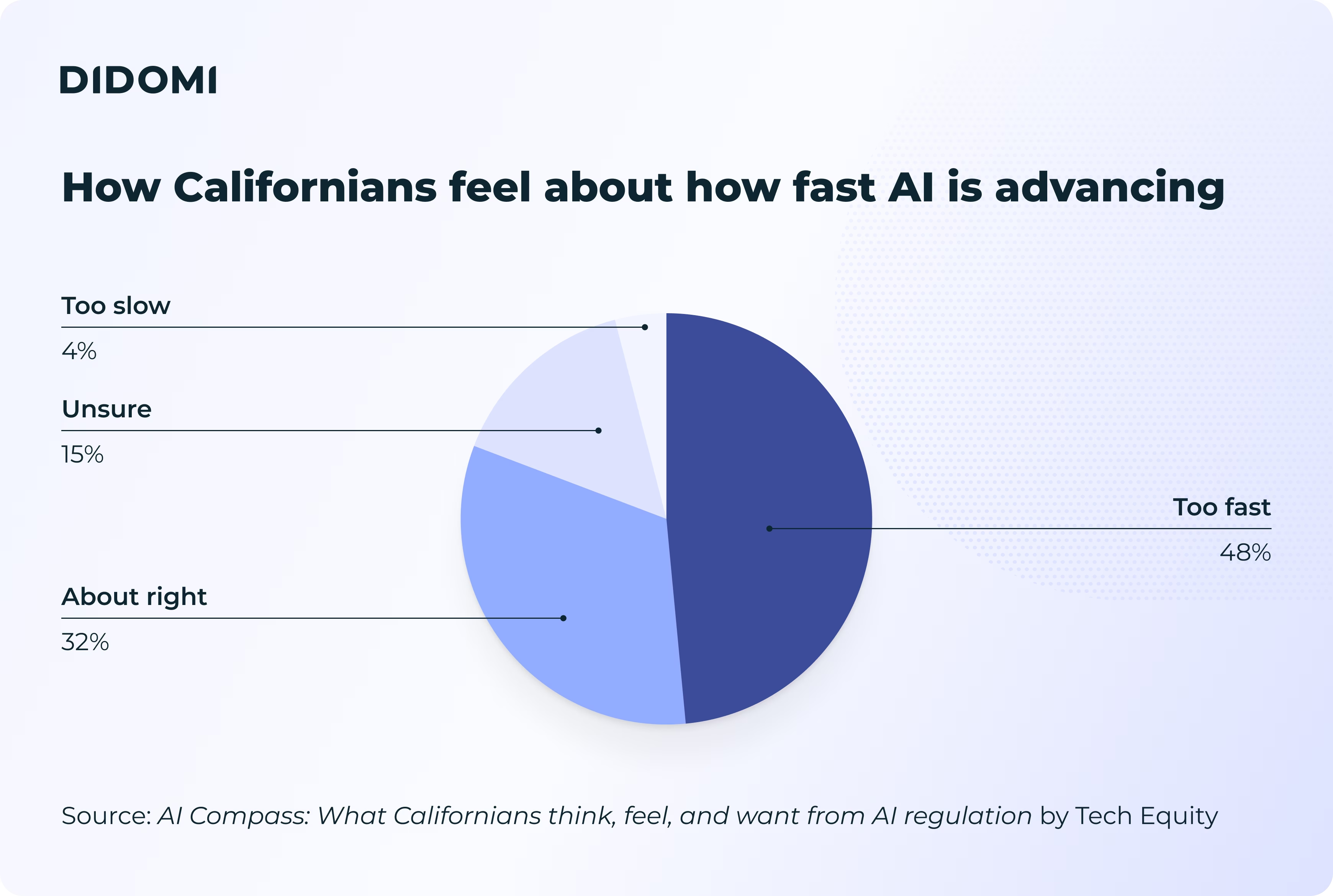

48% of Californians recently polled said that AI was progressing “too fast,” compared to 32% who said the pace was “about right” and 4% who said it was “too slow.” And that's in tech-happy California, home to Silicon Valley.

AI threatens to change privacy as fast as it’s changing everything else. Already, privacy concerns are surfacing, echoing familiar privacy challenges, but at a much greater scale. Generative AI systems are trained on enormous datasets assembled long before modern consent and transparency standards were in place, raising immediate questions about data provenance, purpose limitation, and deletion rights.

Those tensions are no longer theoretical: disputes over training data, likenesses, and personal content appearing in AI outputs have brought privacy principles into direct contact with AI development.

Other issues surface at the point of use. Employees and consumers regularly enter prompts that may include sensitive or proprietary information, often without clear visibility into how that data is retained or reused. At the same time, AI systems increasingly infer preferences, behaviors, and emotional states—forms of profiling that many privacy laws already regulate, but that AI accelerates and obscures.

These dynamics help explain why regulators have begun treating AI less as a novel technology and more as a data governance problem.

Regulating AI: Where privacy laws and AI laws already intersect

As a privacy threat vector, the traditional search engine pales in comparison to the AI chatbot. So do the regulatory challenges.

One lesson we’ve learned (the hard way) from the Internet, however, is that frameworks for regulating transformative technologies need to be in place sooner rather than later, or else you end up with a “train with no brakes” scenario, which many would argue we are already in with AI.

These are still the early days of the ‘AI age’ (...)Whatever we decide to do now will become systemic and potentially irreversible within 20 years.

- Luiza Jarovsky, Co-founder of the AI, Tech & Privacy Academy (source: The Case for AI Regulation, Luiza's newsletter, January 2026)

In the United States, much of the regulation affecting AI does not come from laws labeled “AI” at all. It flows from comprehensive state privacy statutes that already govern how personal data is collected, processed, and used.

As AI systems increasingly rely on personal data, whether to train models, personalize outputs, or infer behavior, these laws have become the first and most immediate regulatory framework governing AI deployment.

States such as California, Colorado, Virginia, Connecticut, Utah, Indiana, and Iowa have enacted broad privacy laws that regulate biometric identifiers, profiling, and automated decision-making, while granting individuals rights to access, delete, or correct their data.

As a result, any AI system that analyzes behavior, processes voice or image data, or makes automated decisions based on personal information is already subject to these requirements under some state privacy laws.

Emerging AI-specific regulations: A taste of what’s to come

Just as early privacy laws, designed around file storage and computer systems, could not fully grapple with the emerging online world and the scale of the Internet surveillance apparatus, privacy laws not written specifically with AI in mind are likely to leave considerable regulatory gaps.

To that end, a smaller but growing number of states are beginning to layer AI-specific rules on top of their existing privacy regimes, increasing both the scope and complexity of compliance.

These laws differ in specifics, but they provide a general sense of how states are approaching AI data practices, transparency, and accountability.

California

California, a leader in data privacy, has moved early and broadly, building AI obligations on top of its existing privacy framework.

- SB 53 (Transparency in Frontier Artificial Intelligence Act) requires developers of certain large AI models to publish safety policies and report serious safety incidents.

- AB 2013 requires generative AI developers to disclose high-level information about the datasets used to train their models.

- SB 942 requires high-traffic generative AI systems to label AI-generated content and provide detection tools.

Taken together, California’s approach emphasizes transparency, safety, and behavioral impact, reinforcing the overlap between AI governance and privacy compliance.

Colorado

Colorado has enacted the country’s first comprehensive, risk-based AI law.

- SB24-205 (Colorado Artificial Intelligence Act) regulates “high-risk” AI systems used in consequential decisions such as employment, housing, and lending.

- The law imposes duties on developers and deployers, including conducting risk assessments, mitigating algorithmic discrimination, and providing consumer disclosures.

Colorado’s framework closely mirrors familiar privacy concepts (accountability, documentation, and user protection) while applying them explicitly to AI.

New York

New York’s AI regulations span safety, transparency, and algorithmic accountability.

- The RAISE Act establishes oversight and incident-reporting obligations for certain powerful “frontier” AI models.

- Separate state-level safeguards govern so-called AI companions, mandating disclosure that users are interacting with AI and implementing protections for emotionally vulnerable users.

- At the municipal level, NYC Local Law 144 requires bias audits and notices for automated employment decision tools.

Taken together, these measures reflect a focus on AI safety, disclosure, and real-world impact, rather than data use alone.

Other state AI laws

Several other state AI laws give a taste of what’s to come and the many flavors of AI regulation.

- Connecticut has amended its privacy law to require disclosure when personal data is used to train large language models, while broader AI legislation has stalled.

- Vermont has repeatedly advanced proposals addressing high-risk AI systems and algorithmic discrimination, even as comprehensive bills have faced vetoes.

- Texas is one of several states that have updated existing criminal statutes to explicitly cover AI-generated child sexual abuse material, using established legal frameworks to address AI-enabled harms.

Despite their differences, these state efforts share a common theme: AI regulation is not replacing privacy law but is being layered on top of it. Transparency, accountability, risk management, and protection against misuse are increasingly applied to AI systems through familiar legal concepts, even as states experiment with new, AI-specific obligations.

Federal AI lawmaking and White House preemption efforts

Privacy laws have filled regulatory gaps and helped keep data collection and use in check. It’s not a perfect system, by any means, but these laws have real teeth and address real concerns.

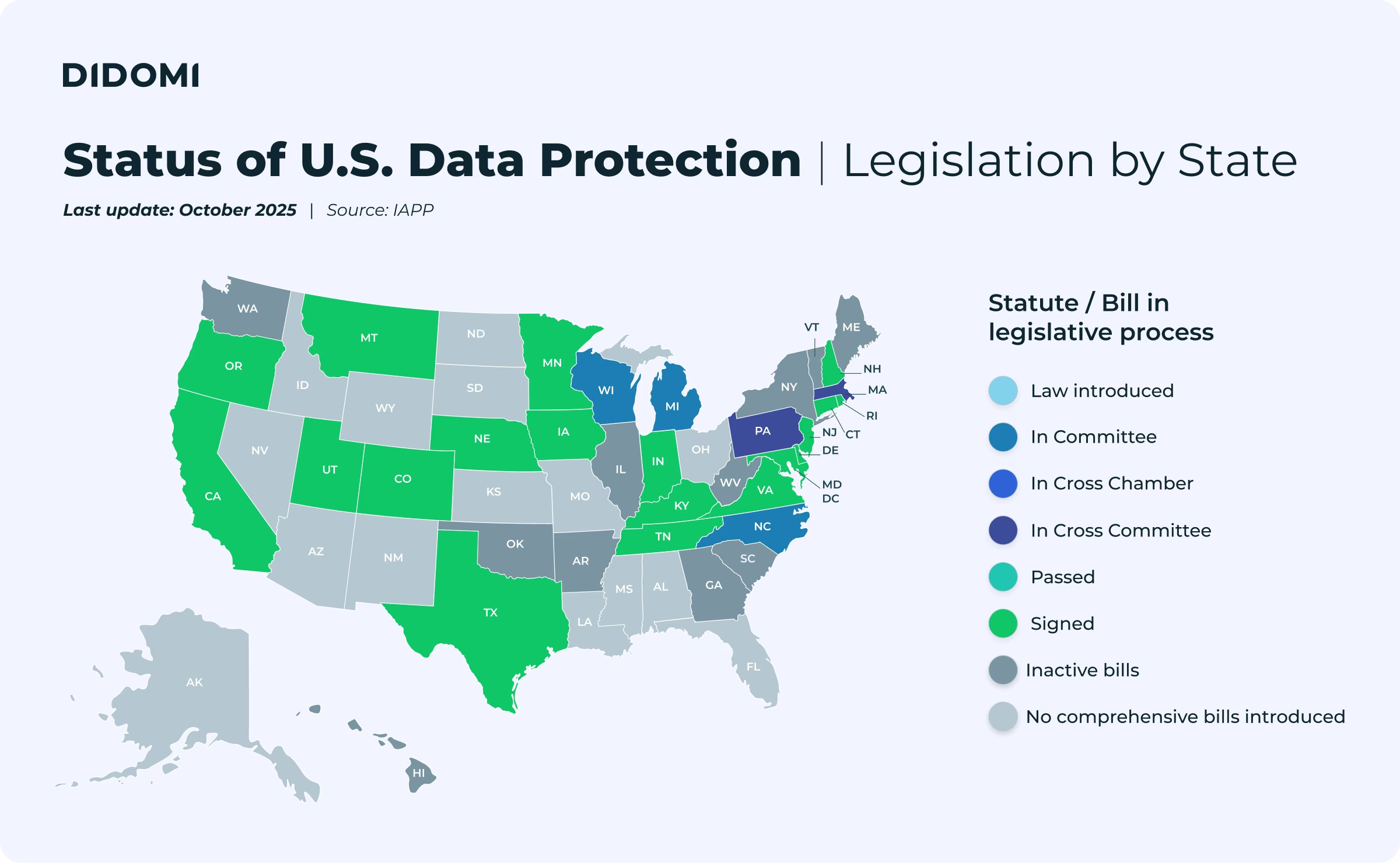

Nearly half of the states (20 in total) have comprehensive privacy laws on the books in 2026. That’s a sign of progress, but it belies the fact that, from a compliance standpoint, companies must deal with an ever-growing patchwork of state privacy laws, each with slightly different nuances and requirements.

{{us-map-link}}

In large part, this patchwork approach to data privacy stems from the absence of a comprehensive federal law. The concept of “federal preemption” has, in fact, been a barrier to adopting a 50-state privacy framework, with legislators from privacy-forward states like California threatening to block legislation that’s not at least as strong as what they already have on the books. As state-level AI rules proliferate, federal policymakers, seeking to avoid a repeat of the AI privacy patchwork, which has been deemed a national security concern and an area of vital national interest, have begun to signal interest in preemption.

This might come as a relief to companies that operate in the U.S., even if it undermines the effect of stricter state-level rules, such as those in California, Colorado, and New York. The prospect of a single federal AI framework promises clarity and consistency, particularly as state approaches continue to diverge. The White House has positioned a unified national approach to AI regulation as necessary to maintain U.S. competitiveness in the global AI race, arguing that the current patchwork of state regulations creates excessive compliance burdens that stifle innovation.

However, state privacy law offers a cautionary precedent. Even well-intentioned efforts to impose uniform standards can take years to materialize, and transitional periods tend to introduce new questions rather than immediate answers. A federal AI regime could simplify compliance in the long run, but in the near term, it is likely to produce a period of regulatory uncertainty as the federal government and states face off in a potential federal preemption conflict.

To stay in the loop with privacy and AI regulatory updates in the U.S., make sure to follow A Little Privacy, Please, a weekly series on LinkedIn where Julie Rubash, General Counsel and Chief Privacy Officer of Sourcepoint by Didomi, covers the latest privacy news with clear and actionable takeaways:

{{a-little-privacy-please}}

Reducing compliance burdens amid the AI arms race

The AI arms race could very well determine the next generation of winners and losers, not only in terms of tech companies and countries, but also for the many smaller businesses that look to use AI for a competitive advantage. Whether there are any brakes on the AI hype train remains to be seen. Based on the speed of AI adoption, we’re all in, and all aboard.

But in this technological terra incognita, the challenge for businesses is as much about managing constant change as it is about predicting which rules and which players will prevail. Tech companies may not be pumping the brakes but from a compliance standpoint, organizations may need to before embracing AI headlong.

With states layering AI-specific rules on top of privacy laws, and the White House signaling interest in federal preemption, companies must navigate a fluid, rapidly changing compliance landscape in which adaptability matters more than predicting the next statute. Technology always moves faster than regulation, and compliance efforts can feel like they’re outdated almost as soon as they’re implemented, leaving companies feeling like they’re always a step behind.

Whether AI regulation consolidates at the federal level or continues to evolve state by state, organizations will need compliance strategies that can adapt as quickly as the technology itself, and companies that succeed in the emerging AI era won’t be the ones that wait for certainty, but the ones built to comply through uncertainty. Didomi and its suite of privacy solutions have been trusted by thousands of companies worldwide throughout the first chapter of the data privacy movement, and will be there to help companies adapt as AI and its privacy challenges write (and rewrite) the next chapter.

.svg)

.jpeg)

.png)