The European Commission has unveiled a new initiative to overhaul how digital regulation works in the EU. Known as the digital omnibus package reform, it aims to cut red tape, streamline compliance, and address consent fatigue.

At first glance, this could sound like a radical shake-up, and even a potential threat to consent management platforms (CMPs), but as we’ll see, it’s more likely to bring clarity than disruption.

Update: Since this article was written, the final version of the Digital Omnibus has been released. Read our updated analysis here.

What is the European Commission's digital omnibus package?

The European Commission has launched an ambitious simplification agenda as part of its new digital omnibus package initiative, a set of reforms aimed at reducing regulatory complexity and modernizing Europe’s digital rulebook.

One of its primary objectives is to alleviate the compliance burden for digital businesses while addressing consent fatigue among European users, a topic that has been at the center of debate for years.

Too much consent basically kills consent. People are used to giving consent for everything, so they might stop reading things in as much detail, and if consent is the default for everything, it’s no longer perceived in the same way by users.

- Peter Craddock, Partner at Keller and Heckman (source: Politico)

To start the process, the Commission has published a Call for Evidence, inviting stakeholders to provide feedback on potential reforms. As a key player in the consent management ecosystem, Didomi will contribute to this consultation, sharing our experience and perspective on what workable, user-respecting consent looks like in practice.

The debate is already heating up. On one side, industry groups are calling for greater flexibility and alignment with the GDPR to enhance the user experience. On the other hand, privacy advocates warn that broadening exceptions could open the door to intrusive tracking and undermine data protection principles.

Understanding the Commission’s objectives

The Call for Evidence for the Digital Omnibus outlines several goals. Among them, two are directly relevant to the debate on cookies and consent management:

- Reducing compliance costs for businesses by cutting through legal fragmentation, clarifying applicable rules, and eliminating obligations where a less costly alternative can deliver the same objectives.

- Reducing cookie consent fatigue while simultaneously strengthening users' online rights by providing precise and straightforward information and options for managing cookies. The Commission explicitly aims to facilitate the use of cookies and related technologies for businesses, increase data availability, and bring cookie rules into closer alignment with EU data protection law (potentially including modernized rules when cookies involve personal data).

Any solution that successfully reconciles these two goals (together with the overarching objective of protecting Europeans’ personal data) is likely to be favored by the Commission, and two potential solutions have been highlighted in public discussions:

- Centralized, browser-based consent management; and

- Lowering the bar for ePrivacy requirements, particularly for certain categories of cookies (e.g., analytics).

Let’s examine each of these proposals before presenting what we at Didomi consider to be the most (and only) viable solution.

Flawed option 1: A centralized, browser-based consent

The idea of managing user consent centrally at the browser level may seem attractive at first glance, but experience shows that it is not such a good idea.

Over the past few years, similar initiatives have been proposed, including the U.K.’s GDPR reform proposals, the industry-led “Cookie Pledge,” and the most recent consent management ordinance in Germany. All have run into the same fundamental obstacle: under the GDPR, valid consent must be specific, meaning that users should be able to make informed choices on a granular level.

To meet this requirement, browser-level consent would need to cover all possible purposes for data processing across the internet. In practice, this would require every actor in the global digital ecosystem, from website publishers to adtech intermediaries, to agree on a common set of standardized purposes. Such an endeavor is simply unworkable.

The only known attempt at creating such a standard is the Transparency and Consent Framework (TCF), developed by IAB Europe. Even this initiative took more than two years of negotiations to establish a framework limited to the field of programmatic advertising, and it remains under heavy regulatory scrutiny, notably by the Belgian Data Protection Authority.

This illustrates the complexity and contestation inherent in creating a global, cross-sector standard.

On paper, centralized consent mechanisms appear simple. In reality, however, they quickly prove impractical. At this stage, the risk of implementing such a system remains largely theoretical. We identified these limitations as far back as 2023:

In essence, the idea is great: Users can set their preferences related to data collection once in their browser, and the technology does the rest, by communicating these preferences to every single website the person visits. That communication occurs in the backend, and users are thus less exposed to consent banners - while their choices are respected.

In practice, however, it’s not so simple.

The lack of standardization makes the idea very impractical. When user choices can reach a high level of complexity, how can we ensure that they are accurately respected and carried over without a clear framework to refer to? From one website to another and one service to the next, the categories of purposes for data collection, third-party vendors, and the overall set of choices might be vastly different.

Then, how can the technology effectively and accurately enforce user choices? Is that consent still valid? Take, for instance, the use of personal data for "analytics" purposes. While one website might label it as 'site performance', another could call it 'user behavior measurement,' and yet another might refer to it as 'visitor insights.'

This disparity in language makes it nearly impossible for technology to consistently and accurately communicate a user's preferences across different websites or apps, further complicating the validity of the consent provided.

- Thomas Adhumeau, Chief Privacy Officer at Didomi (source: Cookies, consent fatigue, and privacy standards: What's next for the AdTech industry?)

This is reinforced by recent statements from Yvo Volman, the Director of Data for the European Commission Directorate-General for Communications Networks, Content and Technology, who has clarified that a default opt-out mechanism requiring users to actively opt in for any form of tracking is not the Commission’s preferred solution. Reading between the lines, the Commission is well aware of the impracticalities of browser-based consent and is likely to explore alternative approaches.

How about AI?

With the rapid development of artificial intelligence, another variation of this centralized-consent vision is emerging: AI agents acting on behalf of users. The idea is that individuals could predefine their privacy preferences, and an AI agent would automatically interact with consent banners accordingly, theoretically reducing “consent fatigue.”

Yet, this approach suffers from the same fundamental flaws. In the absence of a universally accepted standard for purposes and data uses, the margin of error is far too wide for an AI agent to make truly informed and specific consent decisions. How could an AI, for instance, reliably distinguish between “analytics” for audience measurement and “measurement” for marketing optimization? With hundreds of possible processing purposes, the notion of meaningful and informed consent becomes illusory.

Moreover, delegating such choices to an automated agent would require absolute trust, not only in the agent’s interpretation capabilities but also in its neutrality and transparency, which, at this stage, remains an unrealistic expectation.

Flawed option 2: Lowering ePrivacy requirements

A second avenue being pursued by parts of the digital and advertising industry is to utilize the Commission’s simplification agenda as an opportunity to loosen the ePrivacy requirements regarding the use of cookies. The argument being that more flexibility should be granted, particularly for analytics or other “low-risk” processing activities.

This approach is fundamentally misguided.

Even if such a relaxation were granted, consent would still be required for many other forms of processing, especially in advertising, which means that it would have zero impact on the consent fatigue problem. Moreover, the European Commission is highly unlikely to weaken the ePrivacy requirements, given its positioning of the GDPR and the ePrivacy Directive as the flagship of the EU’s digital sovereignty strategy. Lowering the level of protection would contradict years of political messaging and compromise the Union’s credibility as a global leader in privacy.

Under the banner of so-called simplification, the Commission now envisages to withdraw not only the e-Privacy Regulation proposal but potentially even the existing e-Privacy Directive ... without a serious analysis of the risks (...) If e-privacy is dismantled, Europeans will be left with nothing but the Charter to defend themselves while U.S. tech giants enjoy a carte blanche to exploit our data for profit.

- Birgit Sippel, German politician and Member of the European Parliament (source: Politico)

In conclusion, the problem of consent fatigue cannot realistically be solved by centralizing consent in browsers, nor by lowering the standards of the ePrivacy Directive and the GDPR.

Both approaches fail to address the practical and legal realities of data protection in the European Union.

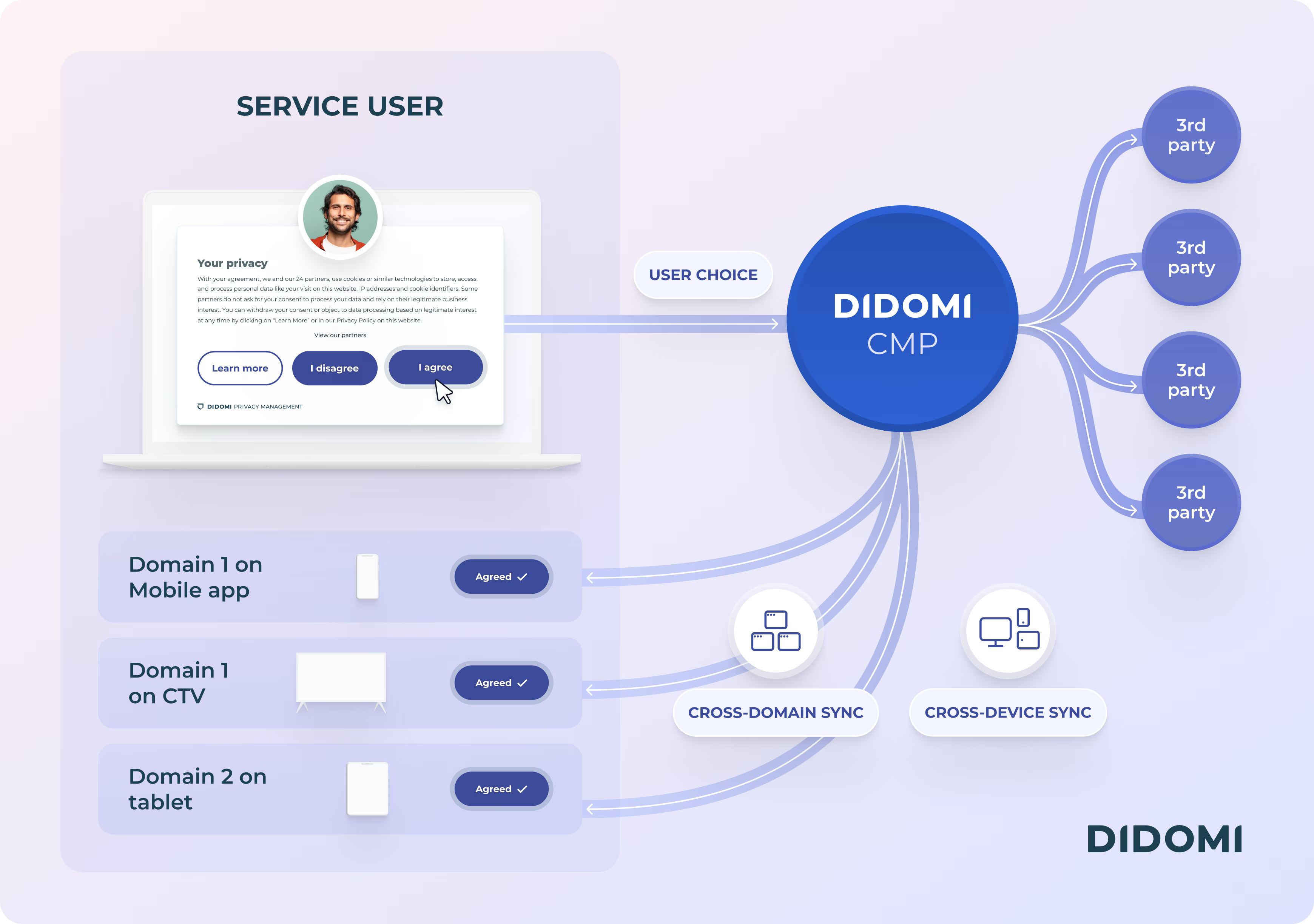

The only viable solution: Shared consent

The only realistic path forward is cross-domain consent. This approach can significantly reduce the number of consent banners users face, without lowering the level of protection for Europeans’ personal data.

To achieve this, a CMP is absolutely necessary in order to recognize the same user across different websites and ensure that their data and tracking preferences are consistently applied. In practice, it enables individuals to express their choices once, ensuring that those choices are respected and enforced across the broader digital ecosystem.

This is a solution we’ve long been providing and advocating for at Didomi. This aligns directly with the ongoing work of supervisory authorities and meets the expressed needs of our clients Unlike centralized browser mechanisms or a relaxation of GDPR standards, cross-domain consent is both legally sound and technically feasible.

In conclusion, this is the only solution capable of reconciling the Commission’s ambitions: reducing the burden of consent banners while upholding the high level of data protection guaranteed to European citizens.

Watch this space as we closely follow the topic and report on its development.

.svg)

.avif)