It wasn’t so long ago that the internet was likened to the Wild West. For minors, not much has changed. From cases of cyberbullying to the spread of pornographic content and a general lack of moderation of harmful content, there’s a global need to protect children in online spaces.

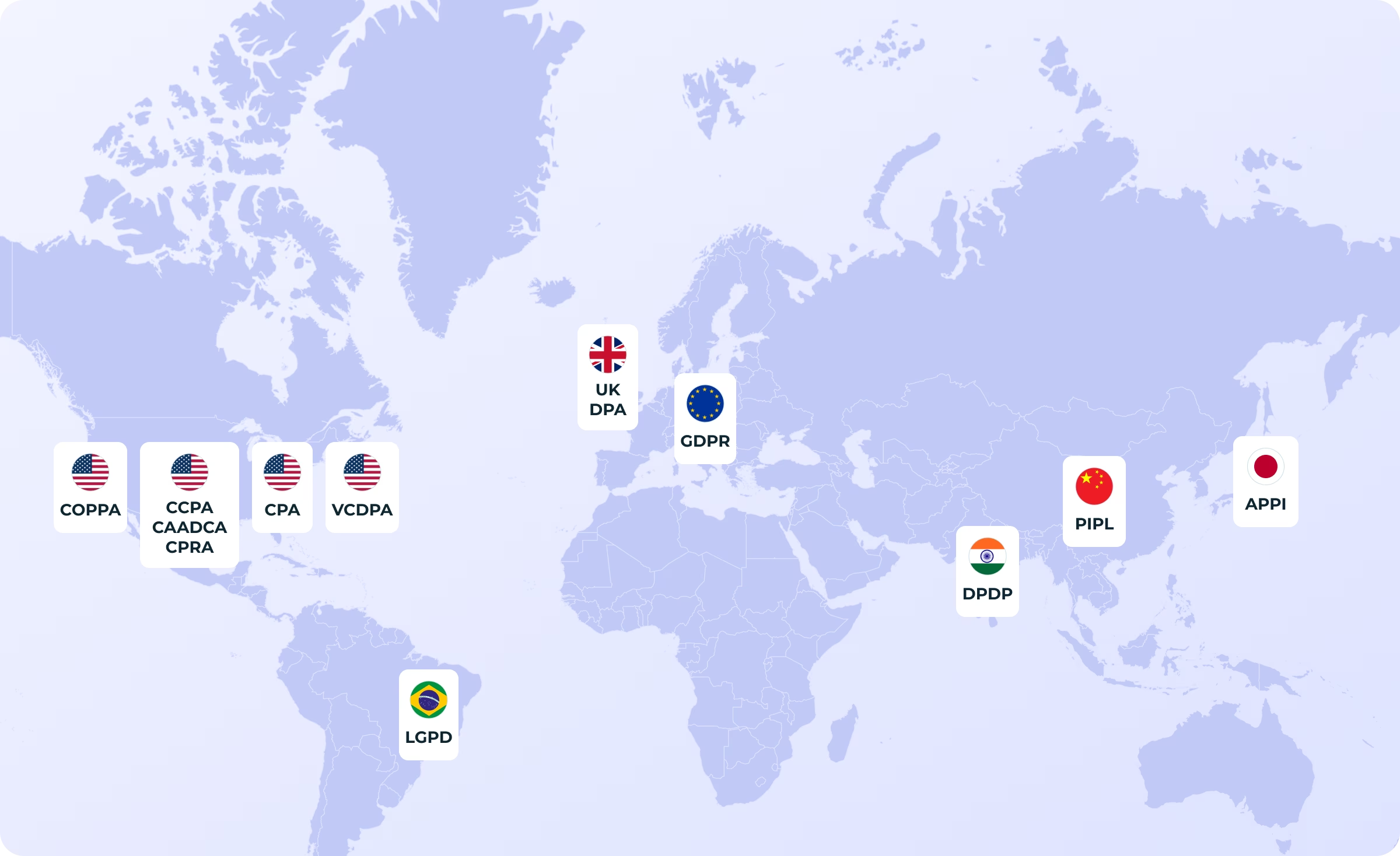

Regulators are addressing this need, giving deserved attention to the privacy rights of underage users in global and local regulatory frameworks. As a result, businesses that collect and process data on underage users are required to comply with a range of regulations, including age-verification laws.

These legal requirements could be the privacy laws of countries/regions where these minors are located (where data privacy laws have an extraterritorial effect) or where the business operates. These laws may also vary based on the organization itself, based on revenue, size, and product/service offerings.

Keeping track of (and complying with) these many requirements can be demanding. In this post, we break down the patchwork of local, regional, and global laws that apply to businesses that collect/process minors’ data.

Privacy laws protecting minors in the European Union (and the UK)

In Europe, children’s privacy is treated as a fundamental right. The European Union and the United Kingdom have both developed frameworks that establish strict consent thresholds, require services to be designed with minors in mind, and impose steep penalties for violations. These rules set the tone for global discussions on underage data protection.

The EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)

In terms of data privacy legislation, the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) is generally regarded as the global benchmark. The GDPR applies to countries in the EU and the EEA (European Economic Area), setting out ground rules for data-controlling entities to follow when collecting/processing data of underage users.

Such information includes sensitive data (e.g., trade union membership, genetic data, biometric data to uniquely identify an individual, data relating to an individual's sex life and sexual orientation; in brief, data about intimate details of an individual's life).

Protection under the GDPR also extends to underage users. Specifically, it sets a baseline age of consent for data processing at 16. However, it grants individual countries the option to lower this threshold to 13 years of age.

Countries like Sweden have adopted this derogation, allowing 13-year-olds to provide valid consent. Spain lowered its threshold to 14-year-olds. Other countries, such as Germany and the Netherlands, adhere to the stricter 16-year threshold. Others, like France, find a middle ground with the French Data Protection Act (Loi Informatique et Libertés), which requires parental consent for users under 15.

But age thresholds are far from the only requirement. The GDPR requires privacy notices to be written in “clear and plain language,” understandable to both adult and underage users. Businesses are also bound by data minimization principles, which means they cannot collect excessive data and avoid practices like excessive profiling, which could expose minors to targeted ads or invasive tracking.

A violation of these rules can lead to fines of up to €20 million or 4% of a company’s global revenue, whichever is higher. Notably, Companies like TikTok have come under scrutiny for potential GDPR-level violations concerning a failure to protect children’s data.

The UK Data Protection Act 2018

Following Brexit, the UK has maintained the spirit of the GDPR through its Data Protection Act 2018, albeit with some adjustments. One such shift was that parental consent applies only to kids under 13. The UK GDPR adopts a similar stance in Article 8.

Further down the line, the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) doubled down with its Children’s Code (2021), also known as the Age Appropriate Design Code, which mandates that businesses design services with children’s privacy in mind. The highlights of this code include 15 age-appropriate design standards that online service providers are required to follow. To qualify as an online service provider, the business must offer a product/service to generate revenue or is likely to be accessed by users under 18, even if they are not the intended target audience.

The design standards include high privacy by default settings, restrictions on data-intensive features such as autoplay, and guidance to discourage minors from oversharing. The code is subject to the full force of the law, and breaches can result in penalties equivalent to those under the GDPR

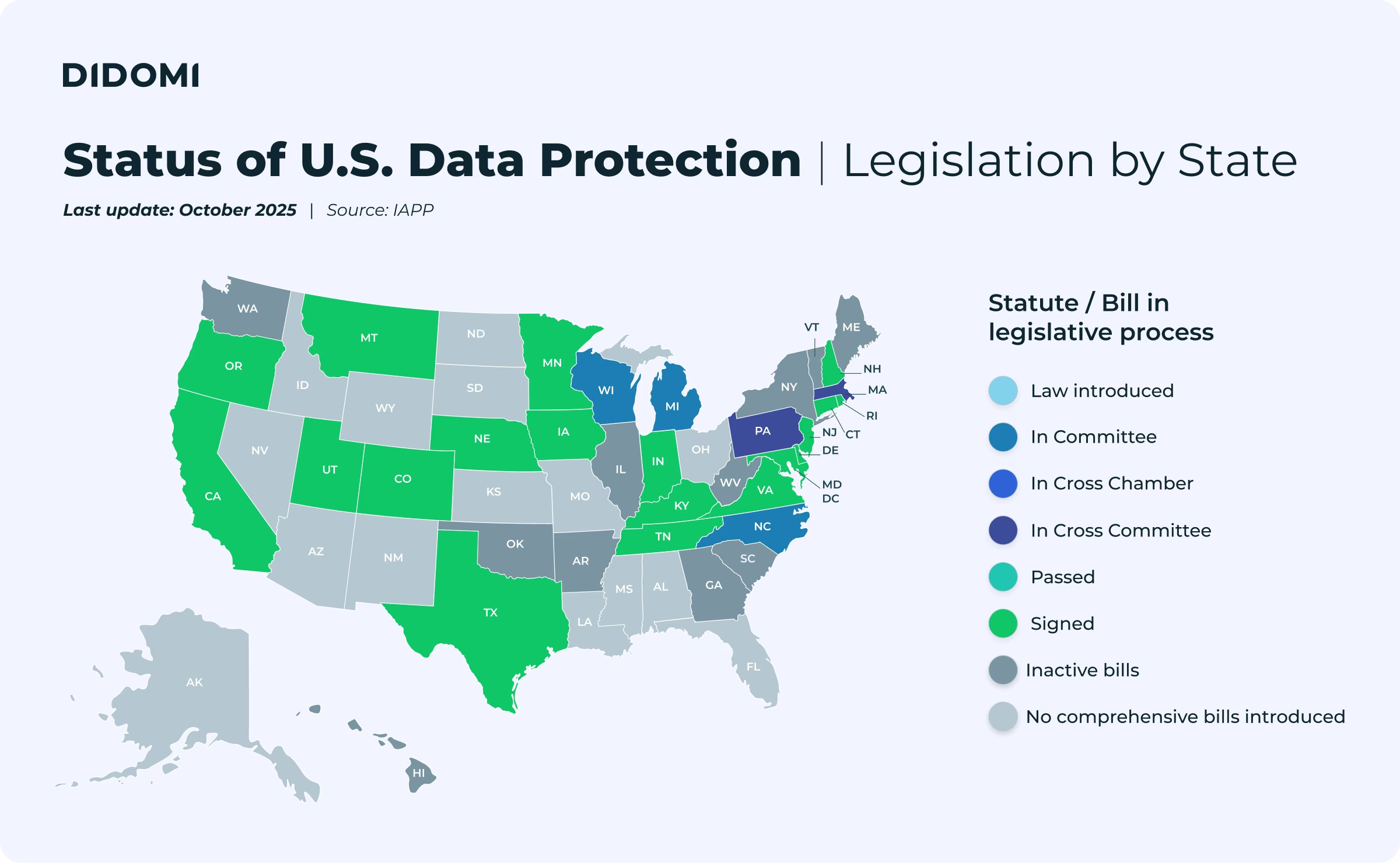

Privacy protection for minors under the U.S. patchwork of state and federal laws

Unlike the single fortress that is the EU’s model, data privacy laws in the U.S. are fragmented. A significant portion of the 50 states has its own privacy laws, as well as several other federal laws dedicated to children’s privacy.

Keep reading for an overview of the U.S. patchwork, or download our dedicated whitepaper on the topic for a full, detailed breakdown of the laws in place and the strategies you can adopt:

Child Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA)

At the federal level, the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA Rule) has been the primary legislation governing the privacy rights of underage users since 2000, when it took effect. The law covers websites and online services directed at children under the age of 13, with a key requirement to verify parental consent before a covered business can collect, use, or disclose a child’s personal information.

In April 2025, the FTC rolled out amendments to the COPPA Rule, which took effect on June 23, 2025, with businesses given until April 22, 2026, to comply. These updates modernize COPPA to address evolving technologies. Key changes include:

- Expanded definition of personal information to cover biometric identifiers and government-issued IDs, in addition to existing identifiers like names, addresses, contact info, persistent identifiers, photos, videos, audio, and geolocation data.

- A comprehensive assessment of when a website/online service is directed to children. The Commission will now consider marketing plans, promotional materials, representations to consumers or third parties, and the age of users of similar services when deciding whether a service is directed to children or not.

- Parental consent rules have been updated to allow text messages to initiate consent and to use facial recognition for parent ID verification. There is also a more detailed parental notice that specifies how the child’s data will be used, who receives it, and why.

- Separate consents are now required for third-party sharing (e.g., targeted marketing or AI training).

- Operators must maintain a written data retention policy. The unlimited retention of children’s personal data is now prohibited.

- Enhanced security obligations, requiring designation of a security coordinator, annual risk assessments, regular testing, and vendor oversight.

- New Safe Harbor Program obligations, including detailed reporting to the FTC and expanded public review of industry frameworks.

- The term “mixed audience” services takes on a new meaning, as a service directed to children (though not as a primary audience), but still needing neutral age verification mechanisms.

California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA)

A subject of the CCPA is required to be operational within the state, regardless of whether its commercial base is located in California. The rule applies to the extent that you’re selling goods/services in California beyond a certain threshold, or otherwise engaging in any commercial activity for monetary gain.

For all the protective cover the COPPA rule was billed to provide, it had certain loopholes that businesses historically exploited to the detriment of underage users. For instance, under the act, once a user self-declared as over 13 (without documentation), many services treated that as sufficient to proceed with collection, leaving room for abuse. That loophole spurred state governments to act. California took the lead with the CCPA, extending protections to minors under 18.

In particular, the act requires companies with actual knowledge of the consumer’s age to honor the following requirements:

- For children under 13, obtain parental consent before selling or sharing their data (for cross-context behavioral advertising).

- For teens aged 13 to 15, obtain the teen’s consent (opt-in).

California regulators have expanded the scope of sensitive personal information in their regulations to include “Personal information of consumers that the business has actual knowledge are less than 16 years of age”. This creates additional obligations to protect children’s data.

These obligations put an additional compliance layer on top of COPPA, reflecting California’s broader approach to consumer and children’s privacy.

The California Age-Appropriate Design Code Act (CAADCA)

The California Age-Appropriate Design Code Act (CAADCA) takes it a step further, mandating that default settings for under-18s' privacy reach the highest level supported by the technology. While its enforcement is currently on hold due to ongoing First Amendment litigation, the Act (initially set to take effect July 1, 2024) applies to services likely to be accessed by children.

Among other things, businesses must:

- Apply privacy-by-design principles;

- Conduct Data Protection Impact Assessment (DPIA) requirements to spot potential risks in online services; and

- Either estimate the age of users with a reasonable level of certainty or apply child-appropriate protections across all users.

California Privacy Rights Act (CPRA)

The CPRA applies to for-profit businesses doing business in California that meet certain thresholds, such as:

- Annual gross revenue over $25M; or

- Derive 50% or more of annual revenue from selling or sharing Californians’ personal information.

Considering that the act defines businesses as “any entity that controls or is controlled by a business”, non-profits that collect data, even if for non-profit purposes, could still fall under its rules in some cases.

When it comes to processing minors’ data, the law imposes specific requirements on businesses. For instance, once a minor declines consent to share/sell their data, the business must ask for consent again at a later date, specifically no earlier than 12 months.

Violations involving minors under the law attract a fine of $7,500 for any violations that may include the data of minors below the age of 16. This layer builds on the fine prescribed in the CCPA, which ranges from $2,500 to $7,500 per violation, regardless of whether the violation involved a minor.

Colorado Privacy Act (CPA)

In addition to data subject participation rights, the Colorado Privacy Act (CPA) Amendments (effective October 1, 2025) expand protections for underage users. The law applies to online services, products, or features offered to a consumer whom the controller actually knows or willfully disregards is a minor (under 18).

Parental consent is required for children under 13, while for teens 13–17, their own consent is required. Consent is required for:

- Targeted advertising;

- Selling the minor’s personal data; or

- Any profiling to make decisions that may impact the child’s legal rights

- Where processing serves a purpose other than the one disclosed at the time it was collected, or

- where the processing continues longer than is reasonably necessary to provide the service, product, or feature.

Under the act, Controllers must also use reasonable care to avoid risks in the service and conduct/document data protection assessments in potential high-risk scenarios.

Virginia Consumer Data Protection Act (VCDPA)

Under the VCDPA, the term “sensitive data” refers to a class of data that controllers are prohibited from collecting or processing without the user’s consent.

In terms of composition, this data category closely resembles the GDPR (data that contains unique identifiers like fingerprints or facial images, inherited or acquired genetic characteristics, physical or mental health information, sexual orientation or sex life, racial or ethnic origin, political opinions or associations, religious or philosophical beliefs, trade union membership or associations).

A notable addition to this list is personal data collected from a known child under the age of 13.

Utah Social Media Regulation Act (as repealed and replaced)

In 2023, Utah passed SB 152 and HB 311 (together the Utah Social Media Regulation Act). The act seeks to provide protection for individuals under 18 by regulating social media companies with at least 5 million global users and enabling social interaction among them.

The law was initially scheduled to take effect on March 1, 2024. But after legal pushback, Utah lawmakers replaced the 2023 act with SB 194 and HB 464 in a new 2024 regime.

Some of the notable requirements in the 2024 regime (to have entered into force on October 1, 2024) are:

- Covered entities must implement an age assurance system capable of achieving at least 95% accuracy in determining whether an individual is a minor.

- Once identified as under 18, minors must automatically be placed under default privacy settings that minimize the collection and sale of their data.

- Must restrict direct messaging features for minors to curb unwanted contact.

- Implement reasonable security measures to protect minors’ data; and

- Covered entities must establish a clear and accessible process through which minors can request deletion of their personal data.

On September 10, 2024, the U.S. District Court granted an injunction because the law (or some parts of it) could limit free speech. As of now, the law’s provisions (including age verification, parental controls, etc.) are on hold pending further judicial review.

Until the courts (or higher courts) settle this constitutional challenge, certain aspects of the law, including the 95% accuracy rule, will remain legally inapplicable.

Texas’ SCOPE (Securing Children Online through Parental Empowerment) Act

The SCOPE Act aligns with the Under-18 protection under the Utah Social Media Regulation Act. Entering into force on the 1st September 2024, all digital service providers, including a website, an app, or a program with users who are known minors under this law, must:

- Obtain parental consent before sharing, disclosing, or selling a minor’s personal information.

- Give parents tools to manage their children’s privacy settings

- Extends protections to minors’ interactions with AI products.

In February 2025, the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Texas granted a preliminary injunction blocking the enforcement of several provisions in the act that conflict with the First Amendment, particularly free speech rights.

The District Court found that parts of the SCOPE Act, specifically its monitoring-and-filtering requirements (§ 509.053 and § 509.056(1)), targeted advertising requirements (§ 509.052(2)(D) and § 509.055), and content monitoring and age-verification requirements (§ 509.057), failed to stand up to scrutiny in light of the First Amendment. Therefore, they should not apply. It also held that §§ 509.053 and 509.055 were unconstitutionally vague.

The above provisions would not take effect until the court decides upon them in a more considered and final judgment. However, the remaining provisions of the law remain in effect.

New York's Child Data Protection Act

Effective June 20, 2025, the law requires digital services to obtain informed consent before processing the data of minors (as defined by the act, minors are children under the age of 18) that is not strictly necessary.

Consent must also be kept separate from other transactions, and this process must provide users with a clear option to refuse as the most prominent choice.

In the state of New York, there is also the Stop Addictive Feeds Exploitation (SAFE) for Kids Act (still under debate), which would impose age restrictions and prohibit algorithmic feeds that expose children to potentially harmful content.

Delaware, Connecticut, and Maryland

Other states in the U.S. are supplementing federal COPPA rules (which cover individuals under 13) with broader children’s data laws.

In Delaware, the Delaware Online Privacy and Protection Act (DOPPA) prohibits operators of websites or online services directed to children, or with actual knowledge that a child is using their service, from processing their personal information for harmful purposes, such as targeted advertising, marketing certain products (e.g., alcohol, tobacco, firearms), or any profiling that may prove dangerous.

The law, however, carves out incidental ad placements (i.e., ads embedded in content) from this restriction (on targeted marketing/advertising of prohibited products). Provided the content wasn’t distributed for the sole purpose of advertising these products, such ads may not be held to have violated the DOPPA.

Connecticut followed with the CT Data Privacy Act (CTDPA) and its 2023 amendments (to take effect on July 1, 2026). The CTDPA protects minors under 18. Controllers are not allowed to:

- Use minors’ personal data for targeted advertising or sell it, even if the controller obtains consent;

- Collect or process such data unless it is strictly needed to deliver the online product, service, or feature in question;

- Use the data for any purpose not disclosed initially at collection, except where the new purpose is both necessary and the same as the initial one;

- Retain minors’ personal data for longer than required to provide the service, except where education technology requires otherwise.

The revised law allows controllers to obtain opt-in consent to process minors’ data where the profiling is necessary to make automated decisions that may affect their rights and freedoms, for instance, in relation to education opportunities or access to essential goods & services.

Profiling comes with restrictions, too. A controller who engages in the profiling of minors must perform Data Protection Impact Assessments (DPIAs), where it is clear that such processing/profiling may result in any heightened risk of harm to minors.

Before the CTDPA’s amendment (the "pre-amendment rules”), a controller would not process personal data of children between 13 and 15 for targeted ads or sale unless:

- They have actual knowledge that the user is in that age group, and

- The controller obtains consent.

For children under 13, the act categorizes their data as sensitive data, triggering stricter protective measures.

Another state that applied its fair share of heightened protections to minors is Maryland. The Maryland Online Data Privacy Act of 2024 (MODPA) outlaws processing children’s data for purposes of targeted advertising or selling data belonging to a minor (under 18s) when the controller knows or should reasonably know that a consumer is a minor.

Even with exceptions to sale and targeted advertising, it would be helpful for a controller to adopt age assurance or verification tools to comply.

A controller would not be required to obtain consent where such processing is reasonably necessary to provide or maintain a service the minor has requested. While MODPA has yet to enter into force (the law becomes enforceable on October 1, 2025), MODPA, much like Delaware’s DOPPA and Connecticut’s CTDPA, reflects a policy shift from the federal under-13 COPPA baseline to a broader under-18 framework, aiming to close the gaps in adolescent protection.

These state laws, together with others currently at the inception stage or presently being developed, present a growing patchwork aimed at protecting underage users against exploitative data practices in the USA.

Children data privacy in other regions

Away from Europe and North America, other regions are developing requirements for businesses that collect and process underage user data to observe.

Brazil

Brazil adopts the principle of "a child’s best interest" as enshrined in the UN Convention on Children’s Rights, as the rule for all decisions and measures to be taken in relation to a child.

The 1992 Child and Adolescent Statute defines a child as anyone under 12 years old and a teenager as any individual between 12 and 18 years of age. In addition, the Brazilian Civil Code states age 18 as the age threshold within which a teenager can be said to have acquired civil capacity.

The LGPD adopts this age threshold, requiring in Article 14 that children’s data (under 12s) is processed in line with their best interests, and only with parental/legal guardian consent. It should also be limited to what is strictly necessary and not stored beyond a single use. For adolescents (12-18 years old), data can be processed without consent. But since the ECA (Statute of the Child and Adolescent) recognizes adolescents as a vulnerable group, special care is still required; controllers must comply with all data privacy principles in the LGPD.

It is worth noting that processing of a child's data in line with the best interest of the child can be interpreted as implicitly limiting manipulative design tactics or dark patterns that, for instance, may lead underage users to share more personal information than intended.

This is because processing must respect the child’s evolving autonomy and should not create undue pressure or exploitation.

China

In China, the Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL) does not explicitly define who a 'minor’ is. However, it treats users under the age of 14 as a sensitive group of users and data belonging to them as sensitive personal information.

This heightens the obligation for businesses. For instance, processing must be for a specific purpose and necessity, with strong protective measures. Article 31(1) of the PIPL imposes this obligation to obtain parental or guardian consent before processing data belonging to underage users.

India

Besides requiring verifiable consent to process children’s (under-18s) data, Section 9 of the Digital Personal Data Protection (DPDP) Act 2023 generally forbids data fiduciaries (widely known as data controllers) from tracking children online, monitoring their behavior, or showing them targeted ads, and outlaws any processing that may be detrimental to their well-being.

However, the Central Government may carve out exemptions from the obligation to seek parental consent or engage in tracking/targeted advertising, once it is satisfied that the data fiduciary processes data in a manner that is verifiably safe.

In such cases, the Government may also specify a higher minimum age threshold (above which consent rules won’t apply).

Australia

The 1988 Privacy Act doesn't have a specific age restriction. That said, the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (OAIC) prescribes that organisations assess whether someone under 18 has the capacity to consent on a case-by-case basis. It further enjoins organizations to assume that persons aged 15 or older have the capacity to consent, unless it is not practical to assess.

With the Privacy and Other Legislation Amendment Act 2024 now in effect, the OAIC is currently developing the framework for a Children’s Online Privacy Code, which will apply to social media platforms and online service providers.

This law will come into force on or before the deadline of 10 December 2026, and will govern how online services for children must comply with the Australian Privacy Principles (APPs)

Japan

As it stands, Japan’s Act on the Processing of Personal Information (APPI) does not define the term “child” or “minor” for purposes of data protection, leaving businesses with the APPI Guidelines issued by the Personal Information Protection Commission (PPC) for guidance on this subject.

The Q&A section of the PPC claims children aged 12–15 are often considered minors without the capacity to assess consequences. It further states that if a minor is deemed to lack the capacity to understand the consequences of consent, then a business must obtain consent from a legal representative (e.g., parent/guardian).

While each case must be assessed individually based on the type of personal data and the nature of the business, businesses, in principle, must obtain consent from a minor’s legal representative in that age group, except in the following contexts:

- When required by law.

- To protect someone’s life, body, or property when obtaining consent from the parent/guardian is difficult.

- For public health or child welfare purposes, when obtaining consent is challenging.

- To cooperate with government duties under law, if seeking consent would obstruct those duties.

Moving forward: A balancing act between data protection and user experience

The challenge of protecting underage users online presents two critical dilemmas that businesses must navigate carefully:

- The technical complexity of age verification necessitates striking a balance between accuracy and user experience. Simple birthdate entries can be easily circumvented, while more rigorous methods, such as ID verification or biometric analysis, may create friction that drives users away.

- The verification of parental consent presents its own set of challenges. Current methods, ranging from credit card verification to video calls with ID checks, each have their limitations. But how can businesses definitively confirm that a parent is truly the legal guardian of a child?

As technology and regulations continue to evolve, businesses will need to stay adaptable, finding innovative ways to protect young users while maintaining engaging digital experiences.

The future likely lies in developing solutions that can verify age and obtain parental consent seamlessly, without creating barriers that compromise the user experience that consumers have grown to expect. To be continued!

{{talk-to-an-expert}}

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

What are the main privacy laws businesses need to consider when handling minors' data?

Businesses must comply with various laws depending on their location and target audience. Key regulations include the GDPR (EU & UK), COPPA (U.S.), CCPA & CPRA (California), and PIPL (China). Many other countries, such as Brazil, India, and Japan, have specific laws protecting child data.

These laws establish age thresholds for consent, require parental approval, and limit the collection and use of data from minors.

How do businesses verify a user’s age to ensure compliance?

Businesses employ various methods for age verification, ranging from self-declared birthdate entry (which is easily bypassed) to more advanced AI-based age estimation, ID verification, or third-party verification services.

The challenge lies in striking a balance between security and compliance while maintaining a seamless user experience.

What are the consequences of non-compliance with minors' data privacy laws?

Penalties vary by law and jurisdiction. Under the GDPR, violations can result in fines of up to €20 million or 4% of the company's global annual revenue. COPPA violations have resulted in multi-million dollar fines, such as TikTok’s $5.7 million settlement. In California, violations involving minors under CPRA can carry penalties of $7,500 per incident.

How can companies ensure they obtain proper parental consent?

Many businesses utilize parental verification systems, including email approvals, small credit card transactions, or video calls with ID verification.

.svg)

.png)