In the Privacy Soapbox, we give privacy professionals, guest writers, and opinionated industry members the stage to share their unique points of view, stories, and insights about data privacy. Authors contribute to these articles in their personal capacity. The views expressed are their own and do not necessarily represent the views of Didomi.

Do you have something to share and want to take over the privacy soapbox? Get in touch at blog@didomi.io

Privacy is dead. And we killed it.

It wasn’t those “evil corporations.” It wasn’t “Big Tech.” It wasn’t the “tech bros” or the “tech oligarchs” or some other shadowy cabal building a digital panopticon to monitor and monetize our every online move.

It was you and me. We killed privacy. We sacrificed privacy for speed and convenience. We traded our personal information for the instant gratification of online goods and services. We chose entertainment and distraction over privacy.

We accepted the Faustian bargain of the Internet. We signed a digital deal with the devil. But the real devil is in the data. Because we don’t actually care about privacy.

Don’t get me wrong. We say privacy is important to us. Very important. We might even believe that it is. We probably need to believe it, emotionally and psychologically, to overcome the massive cognitive dissonance between what we say about privacy and how we act.

We pretend there is a “debate” to be had about the issue, when in fact, that debate ended many years ago, and we conceded.

We’re not even sure why privacy matters. That debate is rarely, if ever, had.

But here's the thing: it doesn't matter why privacy matters or whether we actually care about privacy.

As long as we act as though we care deeply about privacy, companies will have to indulge us.

Privacy–or rather, what I call the “privacy performance”–is baked into the business model now. It’s embedded in the algorithms. It’s part of the user experience. Consumers say they want privacy, and so companies have to deliver it. Or at least, the illusion of it.

Why does privacy matter?

We rarely stop to ask the most basic question: why does privacy matter?

For centuries, privacy has been tied to ideas of dignity, autonomy, and freedom. In democracies, it underpins everything from free speech to free association. If the state or a corporation can watch your every move, your behavior inevitably changes.

Privacy creates space for thought, experimentation, and even rebellion. We’ve understood for decades that changes in behavior occur when individuals know they’re being observed. Research also shows that just thinking someone might be watching us can induce conformity.

But in the digital era, the lofty reasoning behind privacy, like the hollowing out of many of our most sacred democratic values, has collapsed into something more transactional.

Privacy now matters less as a principle and more as a bargaining chip. Although some invoke privacy to defend anonymous online speech, heralding back to the Founding Fathers writing under pen names to express controversial political ideas and protect their identities, they’re just as likely to invoke it when they get spooked by an ad that feels “too targeted” or when their phone seems to know a little too much.

We treat privacy as a right, even though it might be better understood as a privilege that we earn and preserve by protecting it.

That doesn’t mean the concept is meaningless. On the contrary, privacy matters regardless of whether we think of it as a privilege or a right. It’s symbolic. It represents safety, control, and respect. Even if users don’t exercise privacy rights to their fullest, they expect those rights to exist. They want the option, even if they never click the “opt out.”

Privacy, in other words, matters not because it’s absolute, but because it signals power—who has it, who doesn’t, and whether we’re allowed to feel like we do.

Admitting that we have no privacy is tantamount to admitting that we're powerless. “Privacy” becomes a stand-in for “agency.” Consent becomes a metaphor for control. And our most sensitive data represents our deepest desires.

Privacy matters because if we never truly have privacy, then we can never truly be ourselves–the selves that we are when no one is looking, or at least, when we think no one is looking. Only a prisoner is watched 24/7.

The privacy paradox

If you’ve ever visited a website in the last five years, you’ve played the game.

The little box slides up from the bottom of the screen: This site uses cookies. Do you accept? You sigh, glance at the “Manage Preferences” link you’ll never click, and hit “Accept All.” Game over.

A recent YouGov survey found that, when prompted to consent to website cookies, 43% of Americans tend to just accept all by default–virtually the same number (44%) who actively manage their options. That's despite 81% also saying they are concerned with websites using their data.

Nearly 75% of U.S. consumers say they have no control over the personal information that is collected on them, but 54% admit they don't consciously limit what personal data they provide to companies like Facebook and Google.

U.S. News concluded from its 2024 Digital Privacy Survey that 82% of Americans “were concerned about the overall security of their personal data online, although relatively few are taking steps to protect their information”–similar to the disconnect they wrote about in their 2023 survey.

It’s not just Americans: A GDPR study found that 76% of users clicked “Accept All” within the first month of seeing banners, and fewer than 3% ever rejected them. Only 0.5% opened the cookie settings in order to deactivate any of the performance cookies, and only 0.33% disabled one or more cookie categories.

And then there’s AI. The more data-driven our lives become, the more expansive and invasive the collection grows. Algorithms no longer just track our shopping habits; they predict our emotions, our relationships, our identities.

But while technology advances, the story stays the same.

IAPP notes that while consumers express heightened fear of AI’s impact on privacy, they keep engaging with AI-driven services anyway.

I could go on and on, ad nauseam, citing research that shows the paradox at the heart of the privacy debate. But I don't have to. You do the same thing. We all do. We participate in the privacy ritual. We dance the privacy shuffle. We nudge-wink our way past the consent banners.

Companies know you’ll click. You know you’ll click. Still, if the ritual is skipped—if your data is gathered silently, with no nod to your consent—the outrage comes swiftly. Headlines scream about “spying,” lawsuits appear, regulators stir.

That’s the privacy paradox: privacy is dead, but the theater of privacy is alive and well. The curtain must rise, the privacy performance must be staged. Users expect the dance steps, even if they’re just going through the motions.

The psychology behind privacy, cognitive dissonance, and control

Most of us live with a persistent contradiction: we say we value privacy, yet few of us actually take steps to share less or delete the troves of data being collected about us online. And we keep using services that exploit our data.

We want Amazon to recommend exactly what we need, Spotify to know our mood, and TikTok to read our mind.

We crave the frictionless experiences of modern tech and “authentic” brands, knowing full well that entails revealing intimate personal details to private companies. Then we turn around and accuse those same companies of violating our “privacy.”

We want brands to be transparent but don’t hold ourselves to the same standard. We want to have our cake and eat it too. We want to be terminally online without experiencing a terminal decline in privacy.

That contradiction creates cognitive dissonance. And to resolve that tension, we lean on symbolic gestures—cookie banners, toggles, opt-outs—that let us pretend we still hold the reins and to alleviate the very real pain that would come with confronting our cognitive dissonance.

What people crave isn’t privacy itself. It’s the feeling that they're in control of their data.

It’s irrelevant that the choice is meaningless. The token act of choosing is satisfying.

Behavioral economists call our tendency to feel empowered by choices that don’t actually change outcomes the “illusion of control.”

This is the same psychology that makes us hammer the crosswalk button at intersections, swipe away all our phone apps to “save battery,” or mash “skip ad” after five seconds. It’s what makes gamblers insist on rolling their own dice, or office workers hit the elevator button three times when it’s already lit.

None of it changes the underlying system, but the token gesture restores a feeling of agency.

Privacy works much the same way. Clicking “I Accept” gives us a sense of autonomy. It fulfills a deep psychological need: to believe we are active participants, not passive subjects. It’s a type of superstition, or magical thinking, that soothes our anxieties, quiets our contradictions, and allows us to keep scrolling in peace.

When simulation becomes strategy

If consumers don’t actually enforce their privacy preferences and rights, companies could be forgiven for shrugging. Why bother with elaborate disclosures and user controls if the end result is the same?

Because the performance–privacy as a branding exercise–is the thing.

Transparency around data collection directly correlates with brand trust. Most consumers are concerned about data collection and sharing and say they would switch companies over privacy concerns.

Apple has built an empire on the image of protecting privacy, even as its ecosystem quietly harvests information. Mozilla sustains loyalty less through dominance than through its reputation (deserved or not) for treating users’ choices with respect.

Governments are getting in on the privacy act, too.

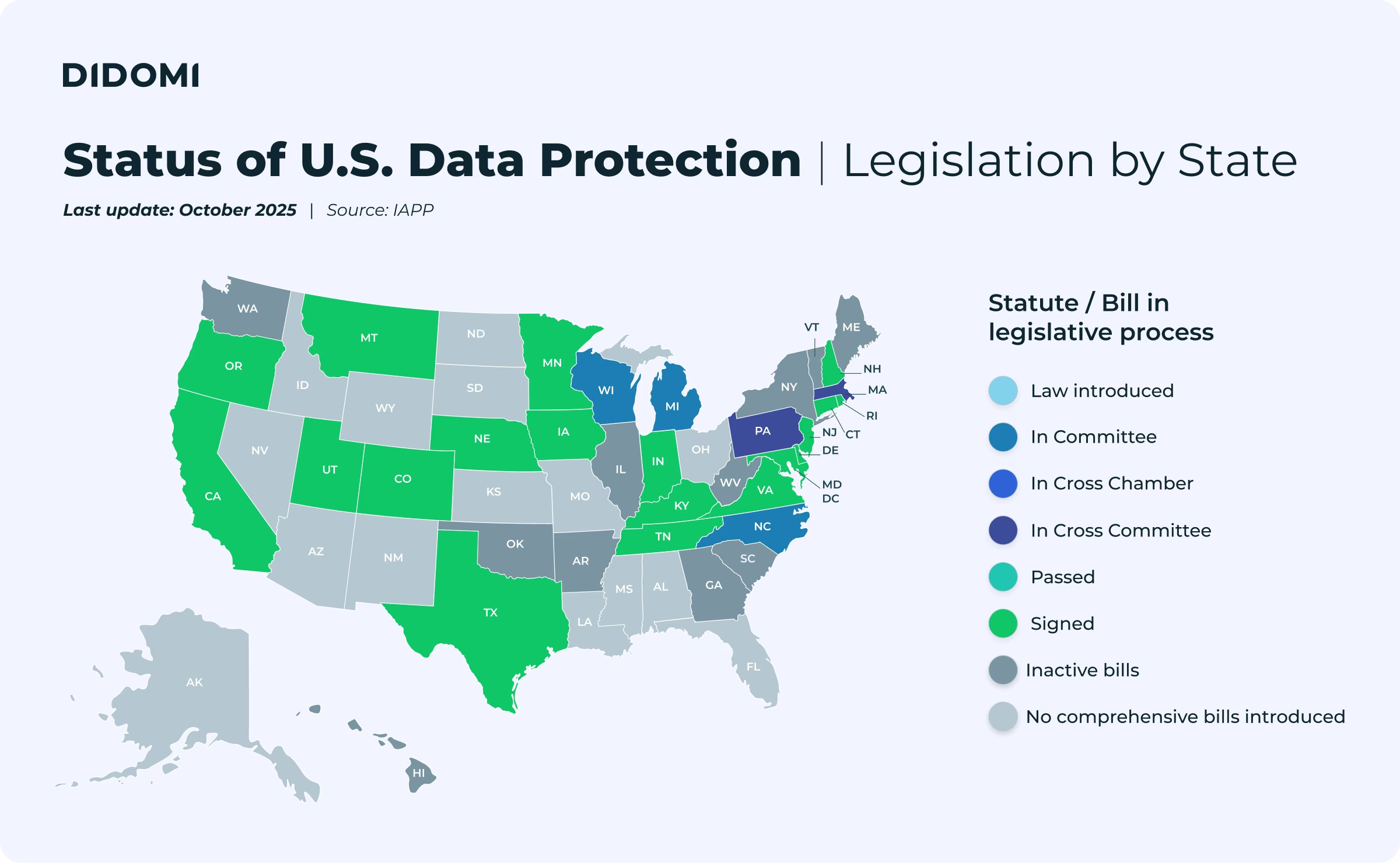

Regulators in Europe and the U.S. are tightening the screws—GDPR, CPRA, BIPA—all demanding clearer disclosures and harsher penalties for deception. They're responding to their constituents in the same way that brands are responding to consumers.

They've read the same surveys and studies that we have. They know that “privacy” polls well and is a winning issue.

The point isn’t whether companies–or politicians–protect privacy in absolute terms. The point is how they present privacy as part of the consumer experience.

A consent prompt, or a policy, that feels respectful builds trust. A buried disclosure or a manipulative “dark pattern” erodes it. Governments have long stressed the importance of transparency. Companies are starting to do the same thing.

When users feel tricked, the backlash is immediate and costly, if not in lost customers, then in reputational damage and regulatory fines. Performative compliance may be symbolic, but symbols are powerful.

Gen Z and Millennials often joke about being “privacy nihilists”—“Google already knows everything about me, so why bother?”—but their actions tell another story. They are ruthless in calling out brands they perceive as exploitative, dishonest, or inauthentic. They may not demand total privacy, but they demand transparency in the performance.

Without the theater, trust collapses. Without the performance, the bargain frays. Without the illusion, the deal with the devil starts to look like a scam.

The show must go on

Privacy is dead, we killed it, and nobody is all that broken up about its death.

We just can’t admit that. We can't admit that privacy has become more of a performance than a principle, that we’re playing a game of “footsy,” a mutually understood but largely symbolic dance where users want to feel consulted, and companies must appear to care—despite both knowing what’s really happening.

We can't say the quiet part out loud. Saying the quiet part out loud–that people don't actually care about privacy–could amount to professional suicide for those of us in the business of privacy.

We say we want more control, when giving up control is part of the bargain we all made when we went online. With every click, every search, and every transaction we only deepen the deal.

We know that the only way to get a modicum of real privacy (and by extension, control) back in our lives is to abandon the internet. We could log off, but we don’t. We could become one of those weirdos who uses a Faraday cage and lives in an electromagnetically sealed hideout. We could cut the cord. We could disconnect, permanently. We could come down from our mountain caves like Zarathustra, stand in the virtual village square on our digital soapboxes, and proclaim that privacy is dead. But we won’t.

Businesses, though, can no more afford to call our bluff than privacy professionals can. If people say that privacy matters, then it matters. If they say that they care about privacy, even if everything they do suggests otherwise, we have to take them at their word, even if that word is uttered with tongue firmly in cheek.

Knowing what we know about data collection–and we all know it–anyone who goes online, for any purpose, can't possibly have a reasonable expectation of "privacy.” But saying so aloud is bad business.

Maybe it's okay, though, to admit that modern privacy expectations are less about actual protection and more about perceived participation. Privacy may be performative, but that doesn’t make it pointless. Far from it.

Perception is reality. As AI expands data collection capabilities, maintaining even the illusion of respectful boundaries becomes more critical.

It's not about fooling people—it's about giving them just enough voice and visibility to let them feel like they have some control over their personal information.

The companies that win will be the ones that treat the privacy performance with performative compliance; that embrace the theater without mocking the audience; that lean into the cognitive dissonance and join the privacy dance.

So I say lower the lights, raise the curtains, and cue the music. The show must go on. And like it or not, we're all players on the privacy performance stage.

.svg)

.jpeg)

.avif)