In the Privacy Soapbox, we give privacy professionals, guest writers, and opinionated industry members the stage to share their unique points of view, stories, and insights about data privacy. Authors contribute to these articles in their personal capacity. The views expressed are their own and do not necessarily represent the views of Didomi.

Do you have something to share and want to take over the privacy soapbox? Get in touch at blog@didomi.io

Let’s be clear once and for all, without too many detours: summer is a malicious invention. And the vacations that accompany it, from July to August, are just one of the worst times to endure in a lifetime, among many. All vacations lumped together, whether taken in general or in particular, from the Arcachon basin to the beaches of Lavandou, from Île de Ré to Puglia, every recreational summer project deserves to be soundly and shamelessly abominated. At best, a stay in Brittany, specifically in Finistère, could help us avoid the worst, provided it’s brief and the temperature doesn’t rise above 20 degrees, with a raincoat at least required. Because summer is that hostile moment of the year when we pretend to be on break, pretend to love rosé piscine, or worse, “orange wine,” in any case pretending enough to cast doubt on something as unthinkable as the concept of civilization.

Luckily, this year, the CNIL, the competent authority, had the good idea to release a new draft recommendation, this time on pixels in emails. No vacation in 2025, then, for data protection professionals. No packs of pitted olives, no criollo chorizo on the grill without the nagging thought of this brand-new administrative object vying for a place among our holidays. Even pétanque this season is played under the watch of the competent authority, whispering Article 6.1.a of the GDPR in our ear as the jack rolls across the clay.

The CNIL has killed summer 2025. If I had their number, I’d text them my thanks.

Barbecue-side consultation

Let’s start with the form, the form of this consultation, I mean. Because it’s always through the form that we learn what the substance will be, at least since 2011 and the invention of Instagram.

Here, one must quote Goethe, if only because it always sounds serious to mention a 19th-century German author. To a young absolutist poet who told him, “I don’t want to know anything about what was said before me!” Goethe replied, “If I understand correctly, you suffice unto yourself to be a complete fool.” The old Goethe was pretty funny, after all.

Be that as it may, with this consultation, which will surely attract multiple contributions, the CNIL seems determined to avoid any association with such a young poet, German or not. Unlike him, it wants to know everything that has been said before, everything. Don’t mistake its intentions: it will listen to professionals and amateurs in data protection; it won’t just do things its own way. On the contrary, it will take into account all feedback, all of it, without exception. I consult, you consult, we consult.

Still, privacy professionals, “privacy pros” as they’re called, would do well to prepare for the likelihood that the CNIL’s final text (probably published between November and December 2025) will look exactly like the draft released for consultation in June. Why? Because, as the CNIL stated in its June 12 press release, the draft was prepared “after discussions with professionals and civil society associations. These discussions notably aimed to better understand practices and address legal, technical, and societal issues.”

Even without being a precocious genius from the Lycée Lakanal or a budding republican schoolboy, I can still read between the lines. And it’s clear: discussions have been ongoing for at least five years. This consultation isn’t a real one.

To picture the dead end, imagine a wedding you’ve been invited to for months, if not years. Invitations sent, menus printed, plates set. Bridesmaids all aligned in the same shade of dusty pink, the groomsmen sporting bow ties from the same boutique in the 3rd arrondissement (Le Colonel), what a bunch of fools. Everything’s ready when the priest, weary, asks if anyone objects to this union. It’s not a real question, just a ritual, a polite reminder that it’s obviously too late, even for the spurned lover fidgeting at the back of the church. No one ever stands up, except in American movies, and not the good ones. This CNIL consultation is exactly that: a closed question with no room for “no,” a tiny window onto a bricked-up wall.

At best, a comma may be moved. But the underlying doctrine will not budge. Consent will be required for pixels in emails, and proof of consent must be shown on a case-by-case basis. Sure, it’s summer, there’s some atmosphere, we’re playing pétanque, fine, it feels “friendly.” But it’s the CNIL throwing all the boules, capito bene tutti quanti? (as they say in Puglia, where summers are unbearable except in Lecce, Italy’s most beautiful city, better than Florence, Venice, or Rome, since Lecce doesn’t suffer from the boredom and tourist varnish of other Italian cities).

A good enemy is one with a name: The soul-stealing pixel

Morality is a complicated, rickety contraption we haven’t aligned since Socrates, which is saying something. Personally, I don’t use misconfigured tech, even if designed to distinguish good from evil. So if you’re expecting here a nuanced moral analysis of the CNIL’s project, brace yourself for mild disappointment, the kind that settles on a Cap Ferret deck when a guest starts talking about France’s national budget to people who only wanted to read Françoise Sagan in peace between bike rides.

No, the idea here is simpler: whether or not it’s morally justified, this recommendation will not be judged for its virtues or vices. It will simply be analyzed as an administrative document that exists, has been born, and will soon have real consequences.

Unlike me, the CNIL agents seem to retain a certain fondness for morality, that variable-geometry tool that makes for poor law. From the first lines of the text, in Section 2, Scope (page 3), it casually drops that “in the context of emails, tracking pixels” are “sometimes called spy pixels.”

Spy pixel? Who calls them that? Apart from the CNIL itself, who? For 99.99% of the tiny fraction of people who know the word “pixel,” it’s the thing that makes a selfie sharp or blurry, not exactly an FSB agent’s portrait.

If I had feedback for the CNIL (since it’s asking for it), I’d request this intro be revised. I’d go full-blown tragic, like a TV news segment during a heat wave. Why settle for “spy pixels”? Better to name the enemy properly: “soul-stealing pixels, bacterial pixels, miniature optical tumors, totalitarian micro-bugs, stigmas of the surveillance society, capitalist sleeper agents.” That would actually scare people. That would have had punch from the start. And it would read better by the pool than a Joël Dicker novel, that Rousseau of Kindle Unlimited, that Enlightenment figure of tanning without tanning lotion.

What does this draft actually say?

That any use of a pixel in an email will now require consent. Sure, there are exceptions, as in every great regulatory epic, but they’re so minor, so symbolic, so faint, they may as well be stylistic flourishes. In practice, for the average marketer, they’re useless. It is better to assume that consent is always required for any purpose. It’s simpler. And in life, simplicity is key; otherwise, you end up splitting hairs and adding to your mental load. And mental load isn’t good: it leads to yoga and meditation, and I, for one, will never wear leggings.

The CNIL, ever mindful of our mental health, even suggests “collecting consent at the same time as the email address itself.” Translation: don’t try to sneak this into your cookie banner. The CNIL knows your tricks.

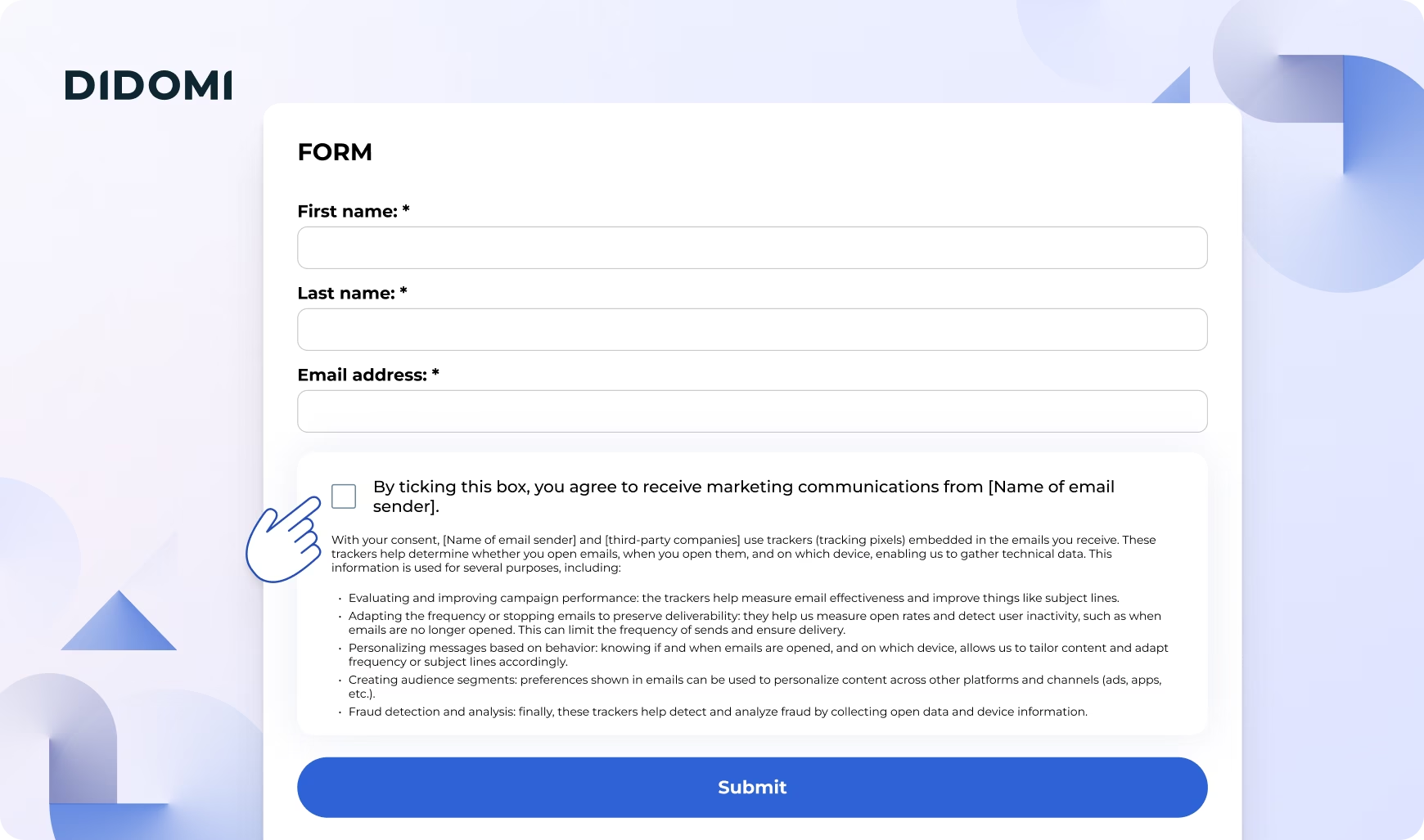

Regarding user information, the CNIL specifies (in a Delon-esque third person): “The CNIL recommends that each purpose be highlighted in a short title and emphasized, accompanied by a brief description.”

Short and brief, got it? But then, in true bipolar style, the CNIL follows with a block of mandatory mentions that would dizzy a spinning top. In the CNIL’s view, “short and brief” means a minimum of 20 lines. Twenty lines of French that make you want to read a Joël Dicker novel (cover to cover) just to rinse your eyes, like using dish soap as shampoo.

This is what’s called a contradictory injunction: “Be concise, but include everything. Be brief, but leave nothing out. Fit eternity into the ephemeral, you tiny worms of humanity.” No wonder DPOs’ mental loads have long exceeded the Eiffel Tower in size. Nietzsche, for that matter, knew a thing or two about burnout, maybe pushed the exercise a bit far.

In any case, it would look something like this, something light:

Anyway, that’s what we’ll have to do for new subscribers after the recommendations take effect. But what about existing email databases? All those contacts who never responded to their spy pixel? What then?

Boss, I slipped on soft law

The CNIL’s recommendations fall under what’s called soft law. The advantage of soft law is that when it prescribes nonsense or impractical measures, you can always try to outdo it in creativity. Unlike hard law, soft law doesn’t ban, doesn’t mandate. Instead, it clarifies, it recommends. Of course, “recommend” contains “command,” which doesn’t inspire much freedom. But in Latin, recommendare means “to entrust insistently.” There’s insistence, yes, but also wiggle room. Like swimming beyond the buoys. Risky, sure, like biking without a helmet, sneezing outside your elbow, or refusing a vaccine because you already had chickenpox in Biarritz in 2013. Wrong, yes, but allowed. In this case, many companies are likely to stray from the CNIL’s recommendation.

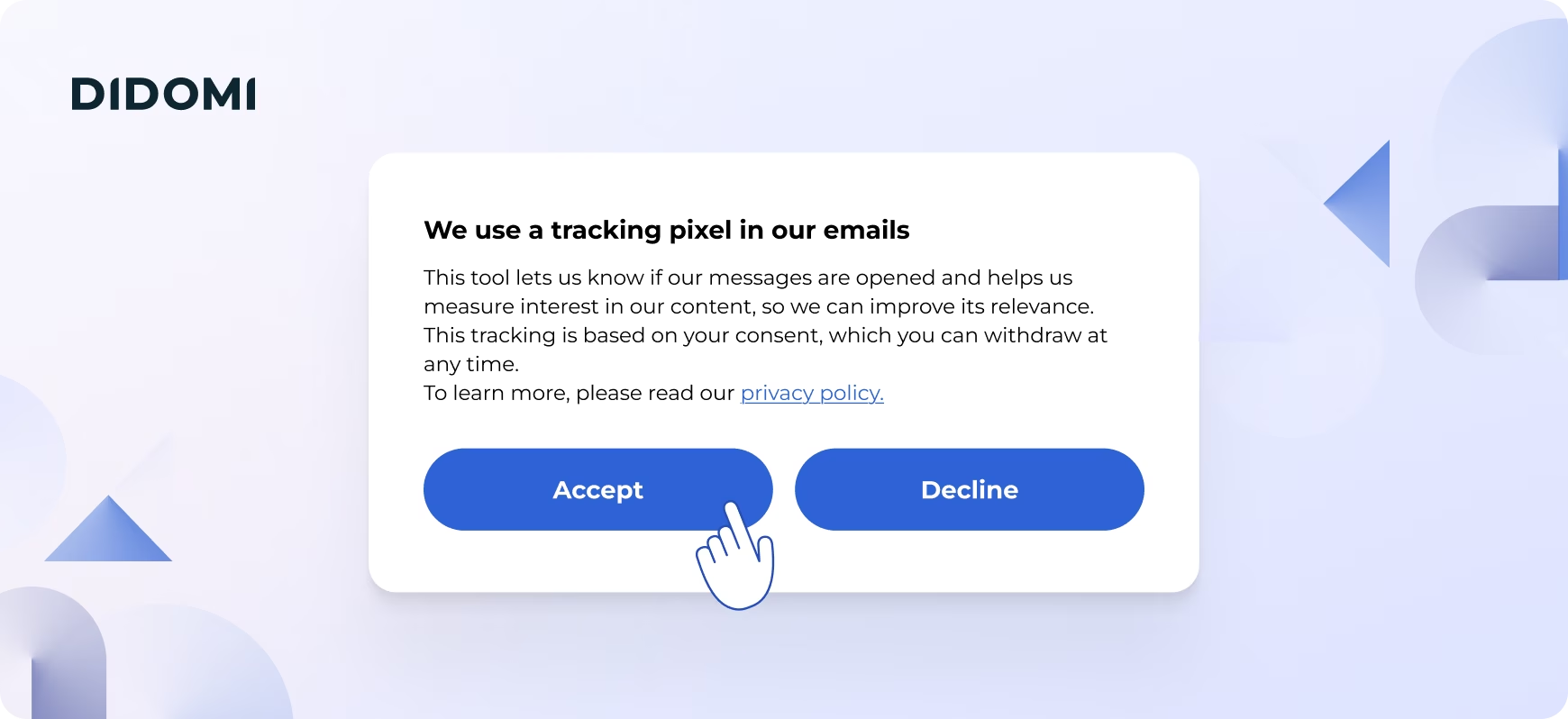

Why? Because if they followed the CNIL literally, sending emails to 21st-century humans asking for consent to a “soul-stealing pixel”, they’d get nothing but scorn and indifference. Who has time to answer yes or no to a pixel between climbing lessons, pottery class, fixing the cargo bike’s rear tire, and the kids’ private school summer party? Life already pushes us toward fleeting bursts of joy, WhatsApp pings, Insta messages.

Instead, why not ask at a better time, when it makes sense, when the user is paying attention? For example, at login. The user is focused, not distracted by a sizzling steak. That’s when you could show a banner, integrated into the user journey. Something neat: “Look, we know you’ve agreed to receive our emails, offers, news, whatever, great. But would you also agree to let us know if you open them? With a tiny, well-behaved pixel that helps us give you more relevant content. No creepy stuff. Just measured intelligence.”

Of course, the exact wording would need fifteen rounds of validation, it’s compliance, not parasol placement. But at least this way, you’d get a 100% response rate. Maybe not 100% “yes,” but 100% something. And if done right, good design, good timing, guilt-free messaging, you could hope for 50–80% consent, like with cookies. Which is not nothing. It’s encouraging. It means continuity. And in this world, continuity is already a lot. Who knows, maybe without realizing it, you just saved a DPO’s skin.

By the way, there’s a typo in Section 2’s last paragraph: a double space between “trigger” and “by.” Please consider this my consultation contribution. I bet that typo won’t survive into the final version. Which goes to show, you can always move the needle, however slightly. After this article, who could still claim it’s impossible to change the world, even at the margins?

Who indeed?

.svg)

.avif)